The unlimited budget of AI: major spend shaping productivity and our economy

Will the $1 trillion going into AI in the next decade be met with real economic value?

A friend recommended the following video from Ray Dalio, founder of investment firm Bridgewater Associates, titled “How the Economic Machine Works”.

The video ends with three takeaways:

Don’t have debts rise faster than incomes.

Don’t have incomes rise faster than productivity (because eventually you will become uncompetitive)

Do all that you can to raise your productivity, because in the end that’s all that matters.

Today, we’re focusing on the last one — productivity, AI’s attempts to raise it, and questions left for what’s to come.

How is productivity measured?

Productivity is a key underlying metric to our economy.

Productivity measures how efficiently goods and services can be produced by comparing the amount of economic output with the amount of inputs (labor, capital, etc.) used to produce those goods. Policymakers are interested in productivity because productivity growth is generally the most consequential determinant of long-term economic growth and substantive improvements in individual living standards. — the Congressional Research Service

Productivity is fundamentally calculated as the GDP (gross domestic product) per worker. The United States has largely outranked countries like France, the UK, Canada, and China in this statistic (see graph below for trends since 1991).

AI has promised, across nearly every industry, that we can do more with less, hence improving economic productivity. Each person you hire will generate more positive business outcomes or you can generate the same amount of outcomes with fewer people. One may assume this new paradigm will improve our productivity, but this hasn’t always been the case with major technological shifts.

The 1970s productivity decline

Economists and technologists have always wanted to better understand the connection between tech innovation and economic impact. In the latest print of Nate Silver’s “The Signal and the Noise”, he writes about the 1970s and the moments where new technology actually inhibited our productivity:

Many thought the computer boom of the 1970s would dramatically impact the nation’s productivity. Instead the era “produced a temporary decline in economic and scientific productivity,” wrote Silver.

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” said economist Robert Solow in 1987

Silver goes on to explain — “The 1970s were the high point for ‘vast amounts of theory applied to extremely small amounts of data’”. He summarizes: We face danger whenever information growth outpaces our understanding of how to process it.

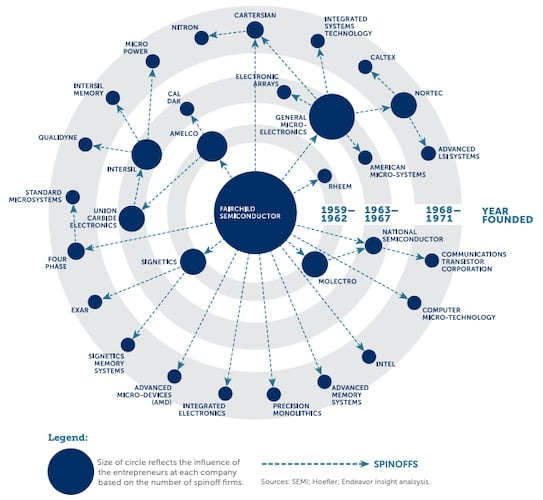

We are amidst an age of outpaced information growth. However, when we look to the 1960s-1970s, while productivity may have declined, the period was a breeding ground for some of the most lucrative and long-lasting businesses in technology today — semiconductors. Fairchild was founded in 1957. Intel was founded in 1968. Through periods of great innovation and misunderstood information may come a short term decline in productivity, followed by longer term periods of sustained growth.

The immediate productivity outcomes of AI

AI has shifted what productivity can look like. As coined by Sarah Tavel of Benchmark, the new call for AI startups is to “sell work, not software”.

I recently listened to a podcast with Bret Taylor, CEO of Sierra and chairman of the board at OpenAI. He tee’d up the pain behind a use case that’s been quickly addressed by many startups, including his, around customer support.

The cost of having direct conversations with all of them [your customers], it's tremendously expensive. Usually, that involves building a contact center, either in-house or with a BPO or an outsourced firm. It probably means that you're overstaffing it to handle peak seasons. And it involves huge amounts of training for the workforce in that call center because every time you have a new product or new process, you need to train everybody, and it becomes a huge cost for your company. — Bret Taylor, Invest Like the Best

Now with AI, setting up a call center can be as easy as setting up any other SaaS tool. Thanks to text-to-voice models from companies like ElevenLabs and AI call companies like Bland, a typical cost center for businesses can become a flexible, scalable, AI-driven solution. The efficacy, accuracy and cost at scale are still in question. Many companies are bundling these technologies, selling the work of a call center, not software.

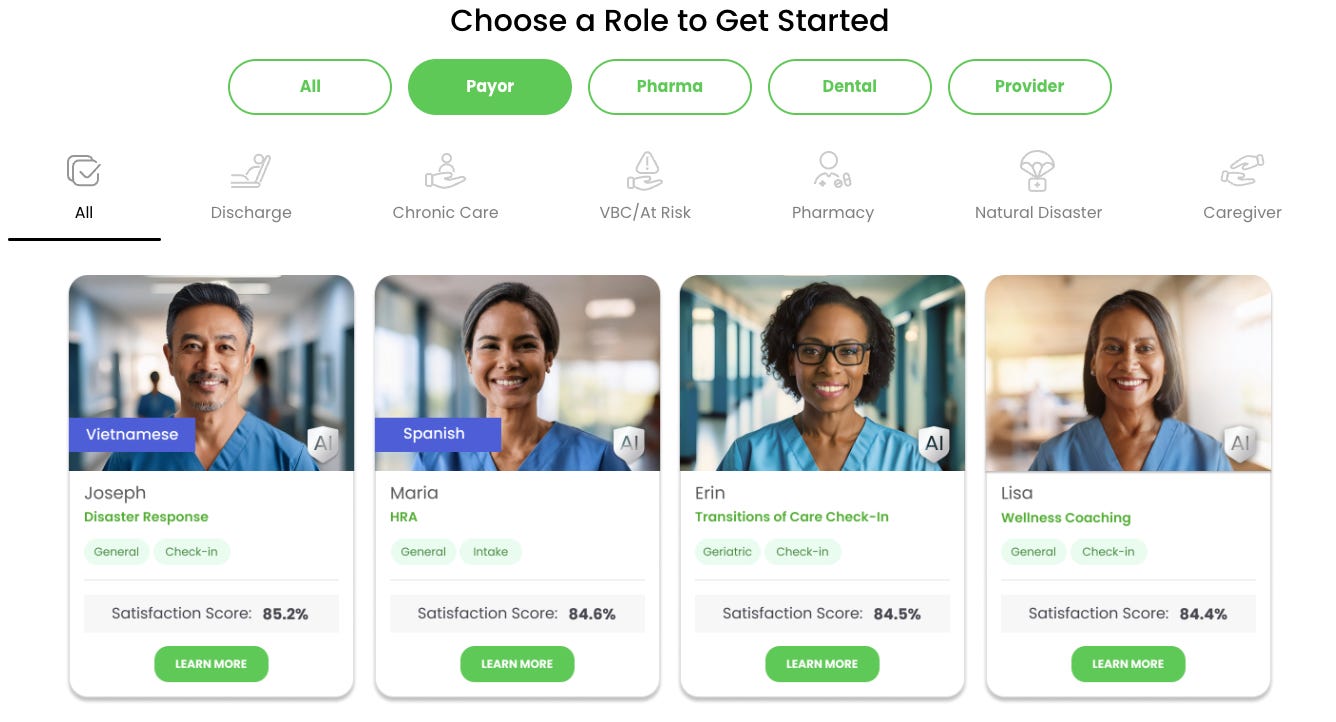

With $17M of fresh funding this week, Hippocratic AI is building agents for a far more expensive field — healthcare. Their team is building secure, healthcare specific agents for roles across pharma, dental, and more. Reporting shows that $82.7B is spent on healthcare admin between payers and providers - which is a fraction of the broader administrative burden on the $4.5T+ healthcare market. Hippocratic can chip away at this preposterous number. More selling work, not software.

There is massive economic value at stake. These are step change level improvements. We are amidst a gold rush in value creation. A senior GS economist estimated that “AI will ultimately automate 25% of all work tasks and raise US productivity by 9%”, thought AI adoption remains nascent.

It’d be naive to not present some skepticism — in a recent Upwork survey of 2.5k full-time workers, 77% who use generative AI in their jobs said it has added to their workload and is hampering their productivity due to time being spent review AI generated output and getting up to speed with new technology.

A reasonable reaction would be to fear job loss and a concentration of value and resources among those able to invest in and shape AI. I share a perspective well stated by a friend of mine Kojo who wrote that startups should aim to “sell aspiration, not efficiency”:

You don't want to fire 20% of your developers; you want to build 20% more features. You don't want to fire 20% of your SDRs; you want to close 20% more deals. The desire to do more with new tools is an aspirational quality deep in our psyche. The most compelling AI products tap into this mentality and lead with aspiration. — Kojo Osei

This won’t be cheap

An estimated $1T is expected to be poured into AI over the next decade.

The trillion dollars pouring in is for everything from hiring top researchers to making commitments with renewable energy providers to power data centers. AI is causing many to rethink the entire compute supply chain in a dramatic way — not just power and energy, but critical minerals like copper, the availability of water used for cooling data centers, and manufacturing capacity to produce everything needed. We are gobbling up resources and shelling out capital in the process.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is investing $65B in building their Arizona fabs for chip manufacturing, creating over 6k jobs.

Google is utilizing a pool of fast-vesting stock grants worth up to millions per person to entice its lucrative AI talent at DeepMind not to leave for competitors.

Amazon invested $4B into Anthropic, a foundation model provider, to bolster their position as a preferred cloud for AI developers.

US VC funding jumped to $55.6B in Q2 2024 from $37.8B, largely driven by investments in xAI, $6B to Elon Musk’s company, and Coreweave, $1.1B to the “AI hyperscaler”.

This week, Microsoft announced its participation in the Global Artificial Intelligence Infrastructure Investment Partnership, alongside BlackRock and others, to bring together $100B to invest in energy infrastructure for AI workloads.

Larry Page, founder of Google, reportedly has said that he would rather have Google (1.94T market cap) go bankrupt than miss out on the value that could come from AI.

This level of activity in the market demonstrates what many believe — there is simply too much opportunity to leave dollars left unspent.

However, the focus on spend may be incorrect. Arguably, the more relevant metric is dollars spent versus company revenues:

“Cloud computing companies are currently spending over 30% of their cloud revenues on capex, with the vast majority of incremental dollar growth aimed at AI initiatives. For the overall technology industry, these levels are not materially different than those of prior investment cycles that spurred shifts in enterprise and consumer computing habits. And, unlike during the Web 1.0 cycle, investors now have their antenna up for return on capital. They’re demanding visibility on how a dollar of capex spending ties back to increased revenues, and punishing companies who can’t draw a dotted line between the two.” — Eric Sheridan, Sr. Equity Research Analyst at Goldman Sachs

Will it be worth it? Let’s look to the Bitter Lesson

In this new world, two things seemingly appear to rule: compute and data — and hence, capital. As Rich Sutton proposed in the Bitter Lesson, “the biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin… the only thing that matters in the long run is the leveraging of computation”.

More compute & more data will result in a higher performing model. A better model will mean more reasoning and understanding, which will enable tackling of tasks to truly shift the productivity levels of workers of all skillsets. And all of this takes a tremendous amount of capital.

One of the best phrases to describe the way I feel amidst all the AI noise shockingly comes from C.S. Lewis, who wrote, “isn't it funny how day by day nothing changes but when you look back, everything is different?”. While today our lives may not feel supercharged by AI just yet, the effects will begin to ripple down, and how we work, live, communicate, and connect will be fundamentally different in the future.

So back to Ray Dalio… This is a moment of productivity explosion. We are doing all we can to increase productivity, because in the end, that’s all that matters.

More thoughts to come. I’d love to chat with any folks pondering similar questions and hear your take. Otherwise, thanks for reading today’s post. I’ll be back next month - turns out longer form, a bit more researched writing is more my speed. See you in October!

Really enjoyed this article! Especially found it interesting to shift the perspective on how AI should help boost the productivity of SDRs, not replace them. Some companies in this space like Nooks AI (https://www.nooks.ai/) seem like they're hoping to solve just that!

Love this analysis. Wages growing faster is what killed heavy industry in this country, especially steel. Computer-based productivity increased wages for those that knew how to harness and cost the jobs of those who could not or would not get with the program — pun intended. Software was always more about the customer than the code — at least it should have been — but engineers and programs could fall in love with code and coding and think little or nothing about the customer. As I described Tio Bobby’s approach to marketing when I spoke at his service, “Make people happy!” Especially those who buy your product.