Punched cards, the US Census, and a brief history on data storage.

How the US Census went from taking 8 years to 2 thanks to punched cards and a number crunching machine.

Happy 2025 (a bit late) and welcome back to Day to Data.

After a brief hiatus, and a fast start to the new year, it’s great to be back to writing. The last two months have been nothing short of crazy in the tech world - from Stargate to DeepSeek, alongside new models and endless promises of how AI will reshape how we work and even how we think about being human.

If there’s one thing we can all agree on, it is that technology is moving at a speed that feels hard to comprehend. There’s a popular benchmark for LLMs called GPQA which consists of multiple choice, Ph.D-level questions. In June 2023, GPT-4 achieved 31%, which is just a bit better than random guessing (25%). Just over a year later, with the release of OpenAI’s o1, model performance surpassed expert level outcomes, scoring a 76% against the benchmark. TLDR; in a year, we went from a kid doing multiple choice questions for fun to an LLM that is outperforming human experts. Dario Amodei said it best, calling it the “compressed 21st century” something like 50 years of research may materialize in 5 years. It’s incredible, terrifying, and mind-numbing all at once.

This past December, I had my own realization of just how far technology has progressed, with a very different, yet somehow more tangible evolution of innovation.

The world before flash drives and floppy disks

In the days leading up to Christmas, I sat with my grandparents in their living room. I grew up in a family of academics and have normalized piles of essays and other tidbits of academia lying around the house. We were in the depths of a conversation when my grandfather was inspired to surface a folder of trinkets he has kept in their basement for decades.

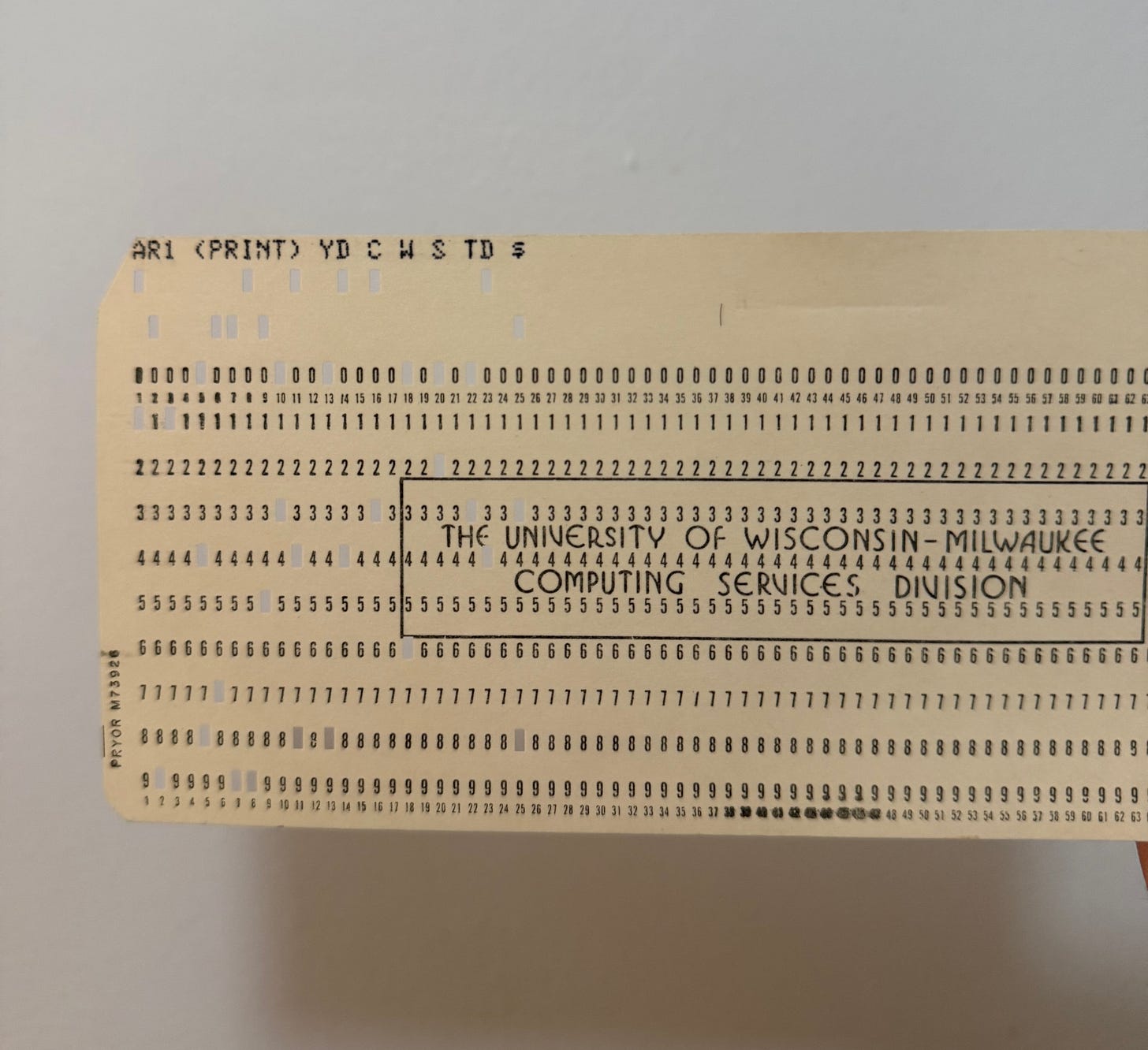

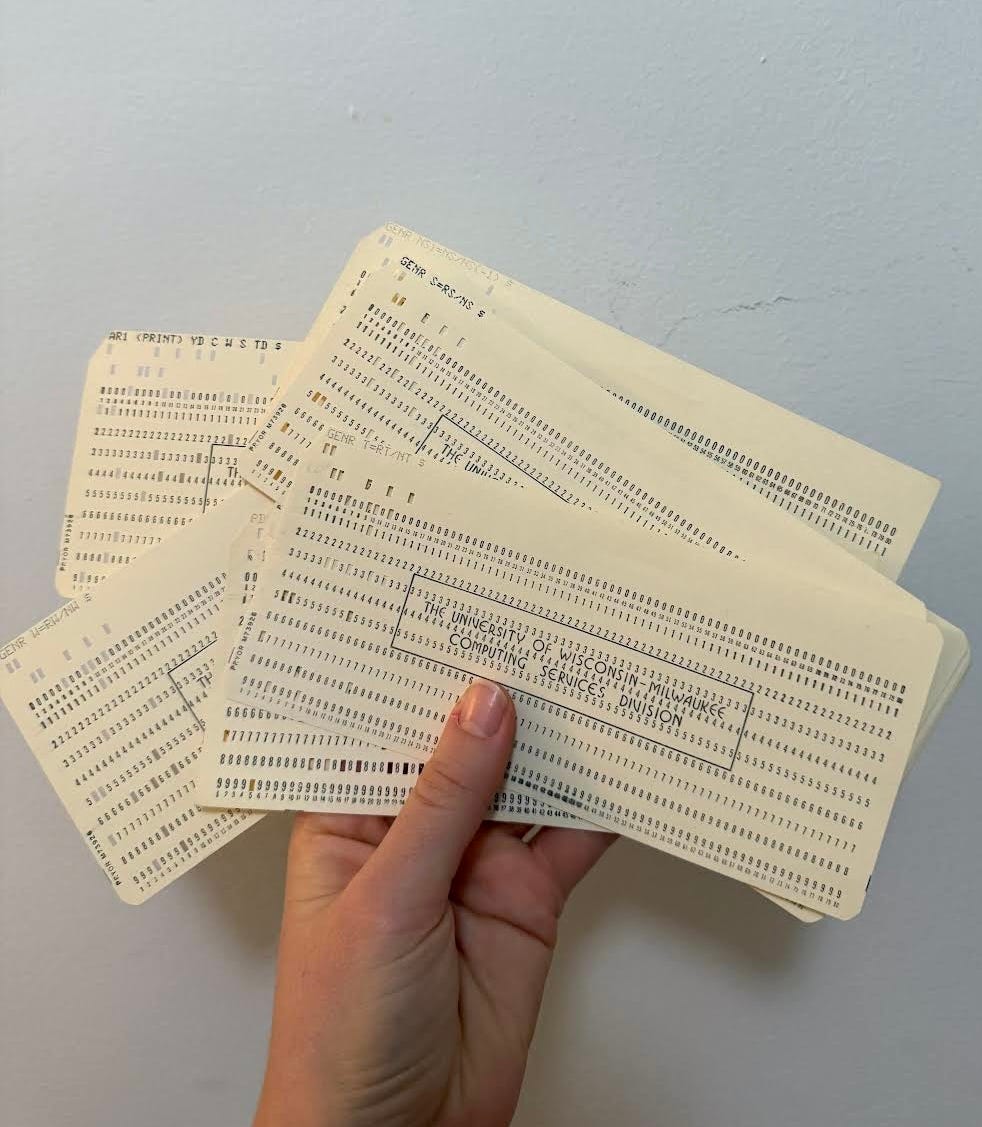

First out of the folder, he handed me old “punched cards” that he had kept from his days of using IBM mainframes while working at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. In the same folder, he had floppy disks, CD ROMs, and flash drives — all remnants of the evolution of technology he saw unfold. So today, you’re in for a brief history lesson on the history of data storage. To get to the punched card though, we have to start with making fabric.

From Babbage to IBM

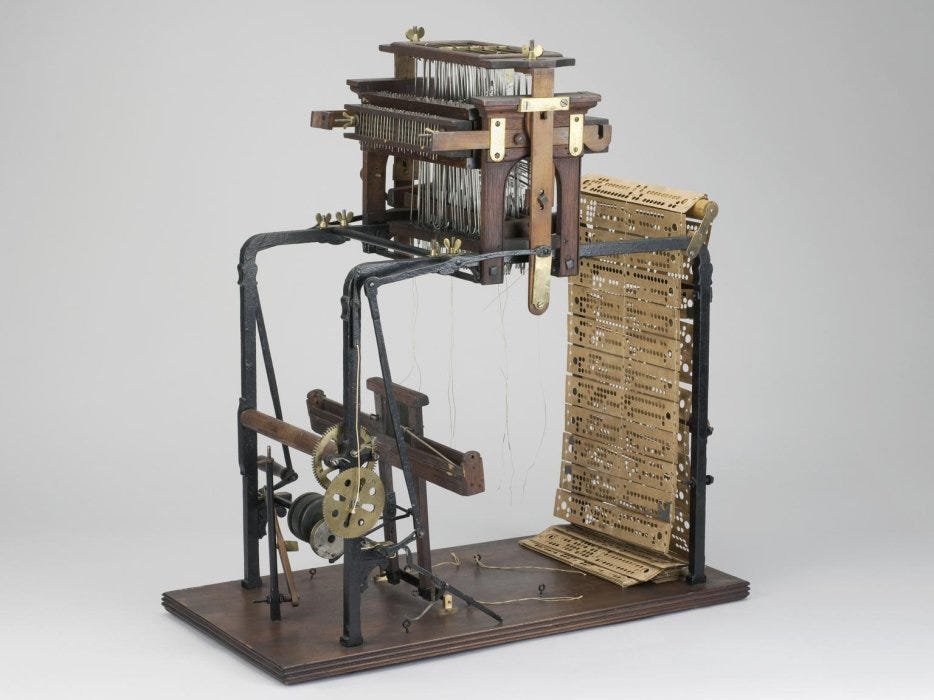

The story starts with a Frenchman. In the early 1800s, Joseph Marie Jacquard was trying to find a faster way to make fabric. He used large cards with holes that when organized together would represent the desired pattern to be woven into fabric. Pins would push thread through the holes of the punched cards, and be prevented from pushing thread through areas where there were not holes, with a shuttle moving back and forth along the loom, resulting in a patterned piece of fabric.

The result was the Jacquard loom, which caused the price of fabric and time spent on textile production to plummet. Jacquard’s punched cards became a physical representation of binary code — punch vs. no punch dictated the actions of the loom, to thread the needle or not to thread the needle.

A few decades later in the 1830s, Charles Babbage, better known as the father of the computer, and Ada Lovelace, aka the world’s first computer programmer began to imagine ways to use punched cards to represent not just binary outcomes, in the form of a 0 or 1, but any type of data. Babbage’s Analytical Machine, which used punched cards as the inputs and outputs of his number crunching machine, unfortunately never came to fruition. However, Babbage and Lovelace’s work led directly to Herman Hollerith and, ultimately, the founding of IBM.

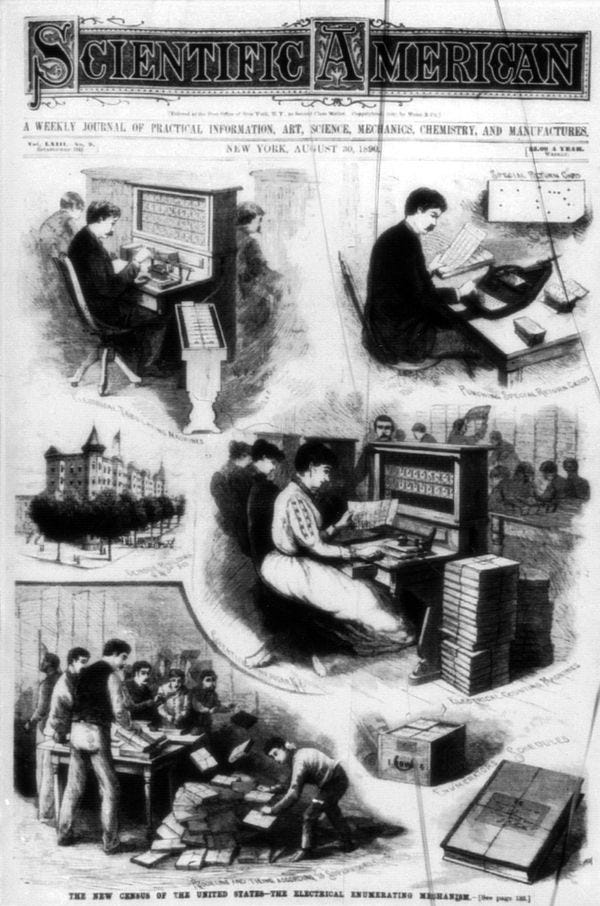

Herman Hollerith & the punched card tabulator

After teaching at MIT, Herman Hollerith left to pursue a statistics role at the U.S. Census. In the late 1800s, counting census results took almost a decade, just in time for another census. Given his knowledge of both Babbage & Lovelace’s punched cards and the complexity of data in the census, Hollerith got to work building a solution.

He went on to invent an electric-powered counting machine. In 1888, Hollerith entered his machine into a contest put on by the U.S. Census for a solution to automating data tabulation and counting, where the winning machine earned a contract to process the 1890 census. For a data preparation task, Hollerith’s machine took 5.5 hours, outperforming his nearest competitor who took 44.5 hours. The 1890 U.S. Census was the first to be counted by Hollerith’s electric-powered counting machine and took only two years, versus taking eight years the previous decade. Hollerith’s tabulation machines ended up completing censuses across Italy, Russia, Norway, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the US, and several other countries.

In 1898, Hollerith founded a business called the “Tabulating Machine Company” to commercialize his counting technology. A decade later, after pressure from the government to reduce the cost of his computing services and time winding down on his patented technology, Hollerith sold his business to a financier who merged Hollerith’s business with two others, resulting in a new company called the “Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company”. In 1924, the business was renamed the International Business Machines Corporation. And IBM was born.

The “modern” punched card

The punched card truly skyrocketed with the creation of IBM. In the mid 1950s, 20% of IBM’s revenue came from punched card sales. And for almost 50 years, IBM’s punch cards held most of the world’s stored data.

To “write” a program, each card was one line of code, roughly equivalent to 80 bytes (my 256GB computer I’m writing this on would require 3.2 billion punched cards to store an equivalent amount of data). As cards grew in complexity, computer programmers continued to tackle more complex problems, ranging from the Census, to science, to complex mathematics, and more.

The 1965 IBM 1130, similar to what my grandfather learned how to use punched cards on, is a far cry from Hollerith’s counting machine from nearly a century prior. The 1130 could be rented for less than $1K/month to be used by researchers, mathematicians, scientists, accountants, and more.

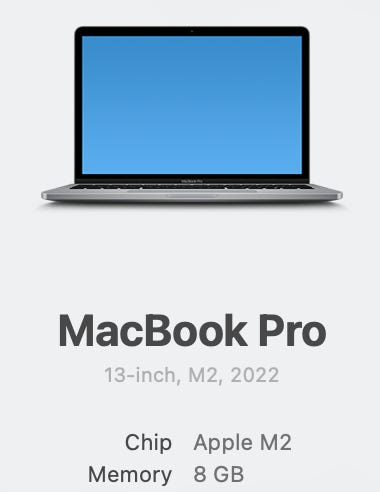

The era of infinite storage

Now, storing massive amounts of digital data is table stakes. iPhones and computers easily have 256 GB of storage. I store over 50K photos on my cell phone. The hundreds of photo albums that sit in 5 bookshelves in my grandparent’s basement could fit on a flash drive no bigger than my thumb. We’ve come a long way from the days of the punch card.

Quick technical note: storage & memory are actually two different things. Storage is used for keeping longer term data, whereas memory is essentially faster, temporary storage for data that needs to be readily accessible at any given time. When it comes to your computer, you may have a device with 256GB of storage, but only 8GB of memory, which is purposeful given memory’s temporary nature. If you’re a Mac user, you can click ‘About This Mac’ under the Apple icon to find out your memory!

I left my grandparent’s house with a pile of punch cards that I plan to frame and hang up in a spot around my apartment. When I arrived home after break, I showed them to my roommate, who said, “you should write about these on Day to Data!”. So here we are. A bit of history, a bit of technology, and just a slice of the innovation that’s helped get us to what we’re accustomed to today.

Thanks for reading this month’s article. More history and deep dives ahead. And a reminder that if you’re thinking about starting something new, curious about startups, or just want to jam on ideas, shoot me a note on LinkedIn — I’d love to chat.

Re Day to data, for one of my grad MIS electives on 1974 I wrote my paper on IBM’s dominance in Europe. As an undergrad I took a one credit course called intro to computing, where IBM mainframes were the only real player, and I learned about Babbage and Hollerith and the history of IBM, and where I started using punch card D’s, which lasted into the mid-1980’s, doing regression analysis on the university main frame. I bought my first ‘portable’ computer, a forty pound Kaypro with two floppy drives — in 1983. At Marquette in the late 1980’s I managed the changeover from one ‘floppy disk’ to two, and then to the original hard drives. Lots of good memories of now ancient technology.