AI's little power problem: are we ready for all the demand that's to come?

More on energy demand, power capacity markets, Jevons Paradox, and a distributed power future. And what happens if we're wrong about it all?

How much do you think energy demand in North America has changed over the last decade?

Barely at all. Until 2023.

In 2023, projected new energy demand skyrocketed, nearly tripling the 2022 forecast. I was at a dinner with some investors a few weeks ago and shared this tidbit. I was met with a response so dramatic I had to fact check myself to make sure I was remembering correctly.

The catalyst behind much of this demand increase is data centers. In Northern Virginia alone, they need “the equivalent of several large nuclear power plants” to meet the electricity demand coming from data centers. Data centers have been around for decades, but in the past few years, it’s become clear that we need plenty more of them.

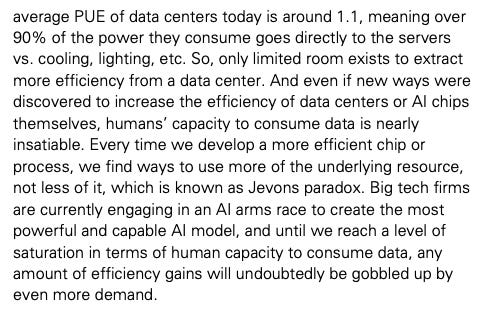

Behind the promised outcomes of AI is a bit of a dirty secret - it is almost unbelievable how much power it requires to not only train powerful large language models but to continue to serve end uses to billions of users around the world compared to previous methods of search and web indexing.

Even on a small scale, the increase in power required is colossal - a ChatGPT query is 6-10x as power intensive as a traditional Google search (prior to their integration of Gemini into search). If the ~200M users ChatGPT users were only sending one query a day on average, it’s dizzying how much demand the platform is putting on our fading energy resources.

On a larger scale, all 2,700 data centers in the US accounted for more than 4 percent of the country’s total electricity consumption, predicted to jump to 6% by 2026. Google’s data center electricity consumption alone jumped 17% in 2023. It’s been estimated that power required to train GPT-4 was equivalent to that of powering 1300 homes for a year (this is just for training - more impact comes from inference).

Power markets are responding. PJM, one of the largest electric grid operators in the US, had their power capacity auction at the end of July. Capacity in this instance means acquiring supply for resources on the grid to meet demand in the future. PJM goes and procures power supply from generators (i.e. one hydroplant commits to providing 1,000 megawatts of power, another for 15k megawatts) to match the demand they expect for the following three years, then a price is set for the power, with a higher price signaling the need for more energy to be produced. At the end of July, PJM’s price jumped to an all-time high, of $269.92/megawatt-day, up from $28.92/megawatt-day at the last auction. The signal was clear — “the market is sending a price signal that should incent investment in resources," PJM CEO said.

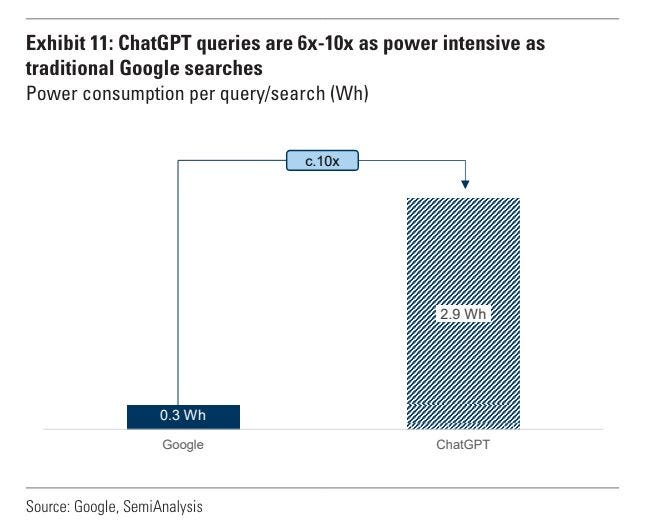

Hyperscalers are getting greedy

In order to feed the beast, there’s a frenzy erupting over precious energy resources across several key players — hyperscalers (primarily Amazon Web Services, Azure, and Google Cloud), power providers, and real estate owners with premium access to the grid.

It is estimated that hyperscalers will capture 50% of the data center market in the next 5 years. Microsoft, Amazon and Google’s businesses have become more dependent on the build out of data centers than ever before. In 2022, Microsoft Intelligent Cloud accounted for 38% of revenue, bringing in ~$75B of $198.27B of total Microsoft revenue. In 2023, it jumped to ~46% of total revenue for Microsoft.

In a world where GPUs are seemingly the most valuable resource, our energy needs may have found a resource that may just be even more valuable over the next decade - land. And not just any land, but land with premium access to power.

The hyperscalers are paying up for the hottest commodity it appears. At the end of 2023, Microsoft paid a family in Wisconsin nearly $70M for over 400 acres of land (which was previously valued by the town at $600K), complete with a pumpkin farm included in transaction. Microsoft has continued to gobble up land in Wisconsin, owning nearly 1200 acres as of this week, to support their plans to build a mega-AI data center hub in the state.

With the impending scale of this build out, hyperscalers are also buying up energy commitments to meet AI demand as well as their carbon-free goals. On May 1, 2024, Microsoft signed the largest corporate power purchase agreement in history with Brookfield Asset Management when they committed to development of 10.5 gigawatts of renewable energy. As of January 2024, Amazon had been the world’s largest corporate purchaser of renewable energy, with more than 500 solar and wind projects globally generating enough power for 7.2 million US homes each year.

The future is distributed

Many are looking to new infrastructure to provide relief to the strained system — virtual power plants may play a role. Virtual power plants aggregate energy that has been produced across distributed generators, such as solar panels on an apartment complex and a wind turbine on someone’s farm. The Department of Energy predicts that 22.5% of peak load demand will be met by virtual power plants by 2030. Going distributed could mean a massive shift in our existing energy markets in a multitude of ways, some best described by Azeem Azhar of Exponential View, quoted here:

“A geographical redistribution of economic power: Regions with abundant renewable resources, such as windy coastlines or sunny deserts, could become new industrial hubs.”

“Seasonal energy arbitrage: Businesses will adapt to seasonal energy patterns. Imagine OpenAI running its AI model training during peak solar months, or Tesla producing batteries when wind power is cheap.”

“Increased grid resilience: A network of distributed energy sources is less vulnerable to large-scale outages, improving overall energy security.”

We’ve been wrong about this before.

In the dawn of the internet age, there was a gold rush, that was likely similar to the AI gold rush we’re amidst right now. There was an urgent demand to meet the energy needs that the new technology would require. In May 1999, Forbes published an article titled “Dig more coal — the PCs are coming”.

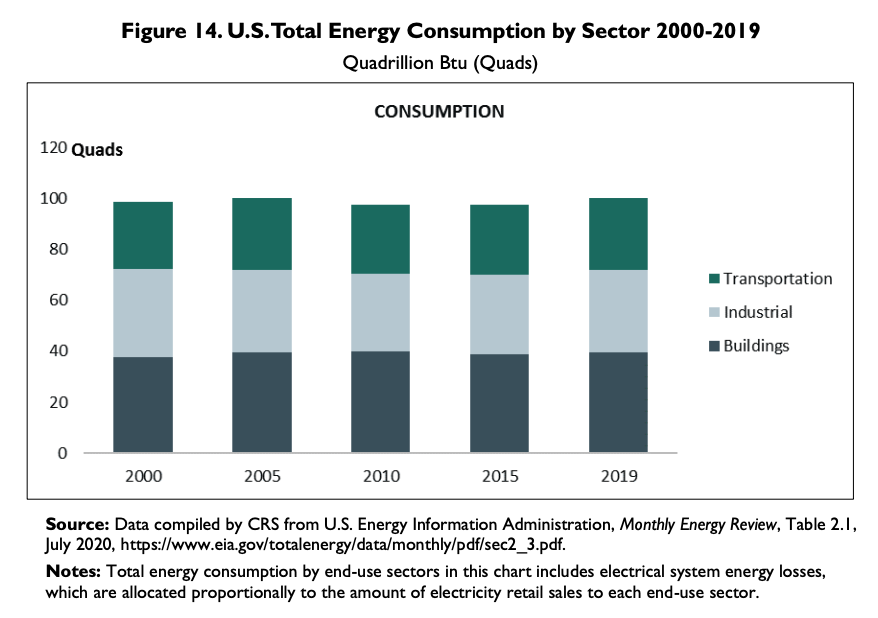

However, much of this expected demand didn’t come to fruition. Take a look at the chart below from the Congressional Research Service regarding energy consumption showing little to no growth in energy consumption from 2000 (after the Forbes article was written) to 2019 (pre ChatGPT).

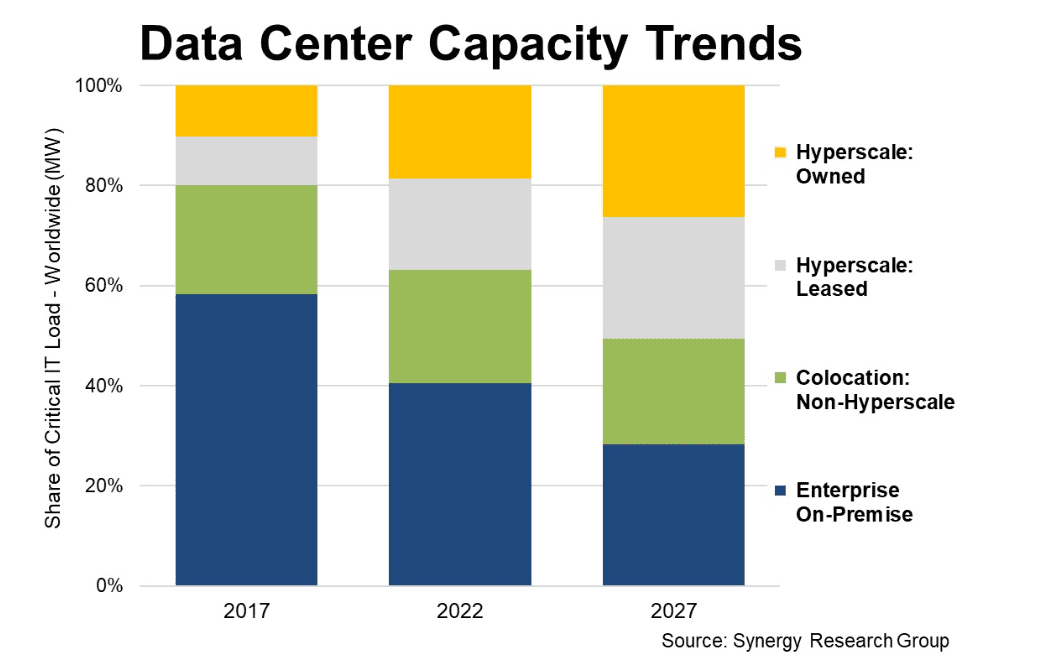

This lack of growth was a response to improvements in both energy conservation (using less) and energy efficiency (finding more effective methods for energy use). Energy efficiency is a good reminder of Jevon’s Paradox —

In the long term, an increase in efficiency in resource use will generate an increase in resource consumption rather than a decrease.

This can be applied to what we are seeing in energy — we’ve improved efficiency, but that just means users are ready to use more energy. So what if we over-respond to this energy dilemma on our hands? When asked about over-investment in AI on an earnings call, Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, claimed that the risk of missing out on the benefits of AI outweighs any belief that they are over-investing. For those drawing parallels to the cloud computing build-out, and predicted energy demand that came with it, Jenny Grimberg from Goldman Sachs asked Brian Janous, prev VP of Energy at Microsoft and now founder of Cloverleaf Infrastructure, for his outlook:

Is our current power grid enough?

It’s unlikely our grid alone will be able to support our energy future. One writer, Justin Etheredge, said it best —

The power grid is the largest, most complex, and most important machine ever constructed. It is the network that enables everything we have in modern society, and yet we are scarcely aware of it until it stops working. It is quite literally the platform that our lives are built on.

We’ve got to be aware of it before it stops working. We are at the precipice of a new era, perhaps one where acute awareness of the grid and our need for renewable energy becomes the norm.

Thanks for reading this month’s Day to Data. I’ve been spending a lot of this summer digging into newer themes and areas outside of my comfort zone - power being one of them - and writing has been on the back burner. Day to Data is on summer vacation, but will be back to regular programming in September. See you all then!

Ford just dropped their electric three row SUV. The really hard trade offs are beginning: energy, water, precious metals, carbon, equality, absolute poverty and economic development and prosperity. Affordability, accessibility and accountability. Something’s gotta give.

So much great info; the opportunity for seasonal energy arbitrage is fascinating