Accept these cookies? Data regulation & the new push for privacy in the United States

America's version of GDPR, the American Privacy Rights Act, is a monumental step in the future of data privacy legislation for consumers and big tech

I’ll start this post by saying I am by no means someone that is an expert in policy of any kind. And I am by no means an expert in data privacy. And yet that’s what we’ll be discussing today! As a consumer of tech products using my data everyday and an investor in companies that are pioneering the way we secure our data, data policy and regulation is a space I’ve been spending lots of time. And it’s been heating up, especially in the United States. In this week’s Day to Data, we’re talking about data privacy and the potential new regulation coming to the United states.

GDPR: the UK’s data protection regulation

You’ve potentially heard of something called General Data Protection Regulation, better known as GDPR. It is regulation, implemented in May 2018, that applies to companies based in the EU that process personal data and to companies established outside the EU that offer their services and monitor user behavior in the EU. If the regulation isn’t complied with, the fines are no joke. As of February 2024, almost €4.5 billion worth of GDPR fines have been paid by ~2000 organizations. The largest fine was a whopping €1.2 billion paid by Meta in 2023 for mishandling user data that was being transferred between the US and EU.

If you want to read GDPR in its entirety, find it here. I’m a few chapters in!

GDPR set a new precedent in protecting users and enforcing businesses to comply with strictly outlined data privacy regulation. There are important tenants to GDPR that made it a major advancement in data regulation.

Some highlights of the regulation —

GDPR requires data protection by design and default.

Data minimization — When implementing a new data application, regulation requires that “only personal data which are necessary for each specific purpose of the processing are processed”.

Accuracy — Personal data must be kept accurate and up to date.

Storage limitation — Personally identifying data can only be “stored for as long as necessary for the specified purpose”.

The right to be forgotten: a user has the right to request the erasure of personal data concerning them “without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay”.

There’s been mixed reviews on how impactful GDPR has been. Consumers just navigate a jungle of “do you accept these cookies?” buttons on every website they enter while in Europe. There’s a new terms & conditions document to read with every new application. There’s been studies on how long it would actually take a consumer to read all the policies they are in agreement with — in the UK, Microsoft Teams would take 2 hours and 27 minutes to read. Even Candy Crush’s policies would take 1 hour and 53 minutes to read. And for businesses, small to medium businesses have been having to increase spend on data privacy teams, cutting into margins, whereas large enterprises like Meta & Microsoft have adequate talent resources and can pay fines when they have to.

The US might get its own version of GDPR

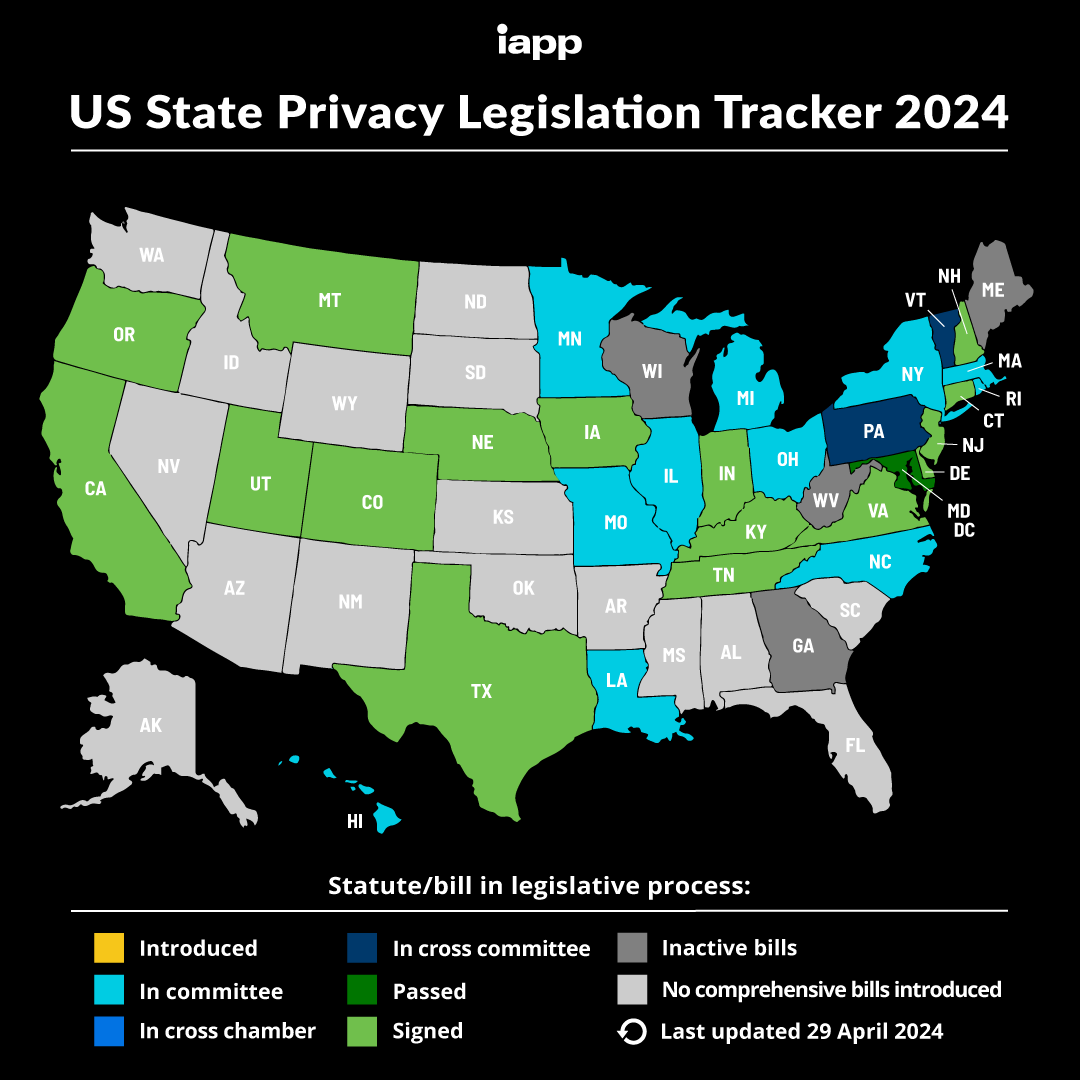

On April 5th, American lawmakers brought forth a proposal for bringing sweeping data policy to the United States through new regulation. This proposal was bipartisan, proposed by Senate Commerce Committee Chair Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.). The proposed act has been dubbed the American Privacy Rights Act (APRA). US states have been more successful in passing privacy legislation. If APRA is passed, it will rival the GDPR to become a leading global privacy standard.

It was a bit of a surprise to much of the public that APRA was brought forward — an American data privacy regulation has been in the works for years with no success. APRA’s predecessor, the American Data Privacy Protection Act (ADPPA), got the farthest along in any approval process by passing committee but failed to pass in the House. There are so many consumer privacy regulations in the works - most recent list here. Last April marked the 36th hearing the U.S. Congress has held on privacy and data security over the last five years.

A few highlights of ARPA include the following —

APRA prohibits the transferring of sensitive covered data to a third party without the affirmative express consent of the individual to whom such data pertains.

APRA would prohibit the use of covered data to discriminate against consumers and provide consumers with the right to opt out of the use of algorithms for consequential decisions.

Small businesses (those making <$40 million over three years or processing the data of fewer than 200,000 individuals annually), and a small subset of other entities, are excluded from abiding by APRA.

Flipping the script: letting users define privacy preferences

I was listening to a podcast with a British lawyer where she said something that stuck with me about how the future of privacy standards could try shift to.

What if, instead of users accepting cookies on a website, websites had to accept the user, based on the privacy guidelines they’ve established for themselves? This got me thinking - what if we flipped the script? Perhaps when you got a new computer, or when you logged onto the internet in a new country, the user could define their preferences in a “privacy passport” of sorts. We could define what we wanted our data to be used for, or not be used for, how we wanted our data to be handled, and how long we wanted our data to be remembered for. Then, we’d navigate the internet and see where our preferences met those of the web. I’d presume two problems with this approach are that 1) users want way less to be done with their data then companies would be willing to adapt to and 2) there’d be a learning curve for users to even define their own personal privacy standards.

What’s next for privacy?

On March 13, 2024, the European Parliament adopted the AI Act, which is “considered to be the world’s first comprehensive horizontal legal framework for AI”. For violators, fines equate to either 7% of global revenue or €35M, whichever is larger (GDPR fines are the higher of 4% of global revenue or €20M). The AI Act will cover a very broad set of companies, including those developing AI systems, deploying AI systems, and those distributing AI systems in the EU. It’s worth dedicating an entire post to the future of AI regulation, in the EU, US, and globally, so I’ll leave this as a cliff hanger for the next data privacy article!

We’ll have to see what unfolds with APRA and the future of data privacy, particularly in the United States and with the rise of generative AI. It’s taken years of legislation to for the US to get to this point, so we’re definitely not at the finish line quite yet. And it will take decades, as it has with GDPR, to study the true effects of such monumental legislation. More to come. Thanks for reading!

Experiencing these multiple “do you accept/reject cookies” events in Edinburgh. More of a nuisance than a time waster, for me at least, so far.

I also see that Wisconsin is one of two or three states with inactive bills in this area of regulation. Along with AI, it looks like privacy is going to be a regulatory nightmare, both to write the laws and regulations and to understand same.